Of course it’s you. Who else could they send? Who else could be trusted? Smoke on the horizon -- hole in the bucket -- voices crying from Milwaukee to Manhattan, ‘Where’s our hero?’, ‘Where’s our Cleanser of the Hidden Sins?’… The cash -- the smile -- the quiet word in the corner -- of course it’s you, Michael, who else could it ever be? But Michael, please, before you sweep, please just hear me out…

STUDY THAT FACE. WHAT is cinema for if not to scan the crags and prairies of a face with the same hunger we probe a scoured battlefield, or a far planet’s unknowable peaks. Study that face, and what does it tell you? It’s a moviestar’s mug, no doubt. It’s George Clooney. But it’s a palled and pallid Clooney. Slightly puffy, bag-eyed, Kentucky tan gone cold. Grey-lit, barely there, tired in the bones. He is playing Michael Clayton, in the final frames of the 2007 film of the same name, a patcher and mender of a sickly order. We saw him, just now, a few moments ago, use his skill and status as a middle-rank bagman to ensnare a murderess. The grubbier tools of his trade have been put to better use, for once. But here he’s sunk in the back of a yellow taxi and the notes of his theme run sombre downward. These are not the scales of victory. Something approaching grief. And still the shot lingers. Nothing but the face. What passes over? A wince perhaps, a shade of embarrassment. Then a half-smile which is the outward mark of a memory briefly cherished. We keep holding. Futility, maybe. Lip-curl of disgust. Might be emptiness, after all. Marrow-emptiness: the kind that trails the slow release of long-held breath, or when an adrenaline high retreats like the tide, and all that’s left is a parched shore.

Where would Michael Clayton be without its ending? A fine thriller, sure. Sleekly plotted. Written well. An actor’s showcase. A reverent tribute, minor-key and soft-pedalled, to earlier noirs (Klute, The Big Sleep). But its end is its making, its consummation. That end lofts Michael Clayton from greatness toward immortality, toward necessity, the sense we would be worse off if it weren’t around. That bonanza, boomtime year, and the Oscars that followed in the winter, had the film squaring off against big, mean, serious, American Epics: There Will Be Blood, No Country for Old Men, The Assassination of Jesse James… They will all endure for their ambition, their baritone recitations of history. Each are united in the theme of human weakness for lucre, joined in suspicion that the hunt for enrichment will turn your heart gangrenous and cruel. In the West, at the frontier, humanity spoils on the sand. Tony Gilroy’s picture – his first as director – is on the other hand lean and mucky and present-day. The soul has soured, riches piled up in its place. It is the end-point of that history, its termination, the starkness of everyday life shorn of myth – most especially those myths birthed by the cinema. The film isn’t in defiance of genre, like those others, but its ultimate expression: the perfect legal thriller, the essential detective story. Perhaps it is appropriate then, with our distance in time – time which is the only true clarifier and worthy judge – that Michael Clayton is nearly two decades old, the age of maturity. And we find, in that age, that it might outlive and exceed its bombastic siblings.

“I’m Shiva the god of death.” This was Michael Clayton’s ending, originally. Gilroy’s shooting script closed on the showdown, our hero triumphant in vengeance. Clayton’s foe trapped and deflated, collapsing to the carpet. A flock of cops closing in. The system holds. Something like justice might, past the credits, be done. He was supposed to walk out with a soliloquy circling his brain, and ours. We get instead a resounding, circling ambivalence. Triumph deflates. Uncertainty comes in, like a fog. Because Clayton is played by George Clooney, he has to wear the ammo-belts and beret of charisma: a charisma made an instrument, tuned to the goal of manipulation and advantage, the confidence that comes twinned in someone who always knows the angle of human weakness, who knows how to prise the sin in others, and wields the wedge to drive it open.

Yet it was a mask always at risk of slipping. It hangs on him heavy, black and wide, like his enormous overcoat. If the film had ended there, as it was intended, the mask would never fully crack and fall. Some part of it would remain, obscuring. Except we get the final flash of inspiration: charisma left on the sidewalk of Sixth Avenue, coughing in the day-waste of traffic. Clayton, bare at last and pooled on the taxi leather, letting reality crowd in and flow over. Just out there, through the sliver of cab window and unfocused rear-view, is a New York already primed to collapse. In those offices – endless, upwards – the subprimes are defaulting. Those with the nose and drive to sniff the implosion are placing their bets. The gash has been made. The treasuries are bleeding. Soon foreclosure notices will start to slip off police department presses. Michael Clayton debuted in the world in October 2007. The disaster had already begun. “You’re so fucked,” Clayton says. Didn’t he warn us?

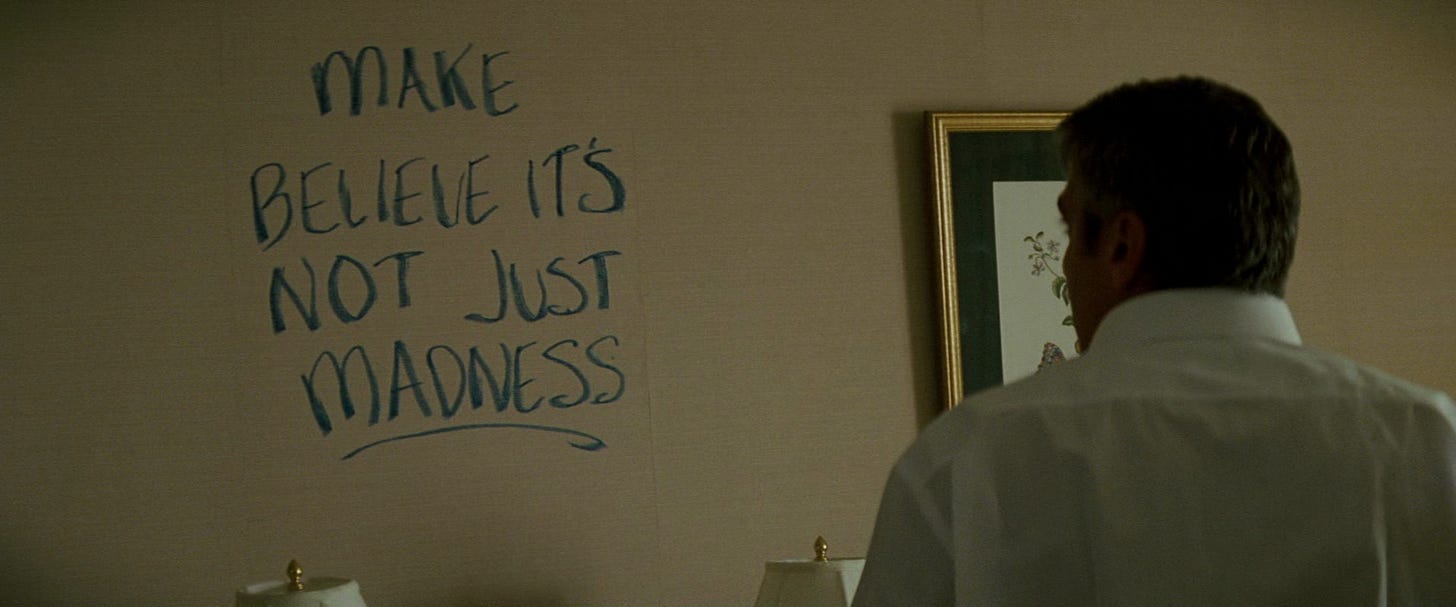

…I’m begging you, Michael, make believe it’s not just madness, because it’s not just madness -- I mean, yes -- okay, yes -- elements of madness -- the speed of madness -- yes, the occasional, euphoric, pseudohallucinatory moments that, yes – agreed -- fine -- distracting -- nostalgic -- all of that -- but that’s just the package -- the plate -- think of it as a tax -- The Mania Tax -- The Insanity Tax…it’s the freight -- the weight -- it’s the price of the show…

BENT CONGRESSMEN, BENT COPS, bent executives, bent lawyers. Thalidomide babies. Syphilitic sharecroppers. Teflon runoff in the ponds. Chromium 6 coming out the taps. Plutonium on the wind. Wisconsin well-water laced with weedkiller. This is your world, and it cries out to be soothed.

The firm of Kenner, Bach & Ledeen is here to stifle that cry – one of those enormous semi-anonymous houses whose purpose is to bulk widely in the door to any kind of remedy for the afflicted, the bereaved, the lonely. It keeps a stocked arsenal, bottomless coffers, vast battalions at its disposal. Michael Clayton (Clooney) is one of those troopers. Once a bright-spark litigator, he’s been shuffled sideways by his boss Marty Bach (the great Sydney Pollack) and acts as a blurred man, one foot either side the line of legality. His piecework is tax dodges, press gags, shoplifting housewives, motivated strippers. Greying handsomeness and a thick wad of cash are his weapons. There are limits to his powers, regions where he cannot venture, encounters in which his charm, his calming gifts, turn impotent. Here is one –

For six years KB&L has been defending an agricultural giant called U/North, makers of a toxic defoliant – “tasteless, colourless…does not precipitate.” The death toll stands at 468. Survivors are pushing a class-action suit against U/North. Their only representative, in the film, is Anna (Merritt Weaver): breathtakingly young, shrinking yet brave, skin like butter. “A miracle,” says Arthur Edens (Tom Wilkinson), KB&L’s attack dog on the case, “God’s perfect creature.” It looks like Arthur has gone deranged for Anna. There is video proof: an ageing maverick pathetically stripping his clothes off in a deposition room, confessing his love. But the love comes second. What looks like derangement has a reason. Arthur has found a document that’s turned all his efforts meaningless. Worse than meaningless: callous, conniving, evil. He has been made, against his will, the agent of coverup and conspiracy. It’s caused a clack in the brain, an outpouring of contrition. Arthur’s brilliant monologue – his plea, his remonstrance – runs channels through the film like magma on cold earth.

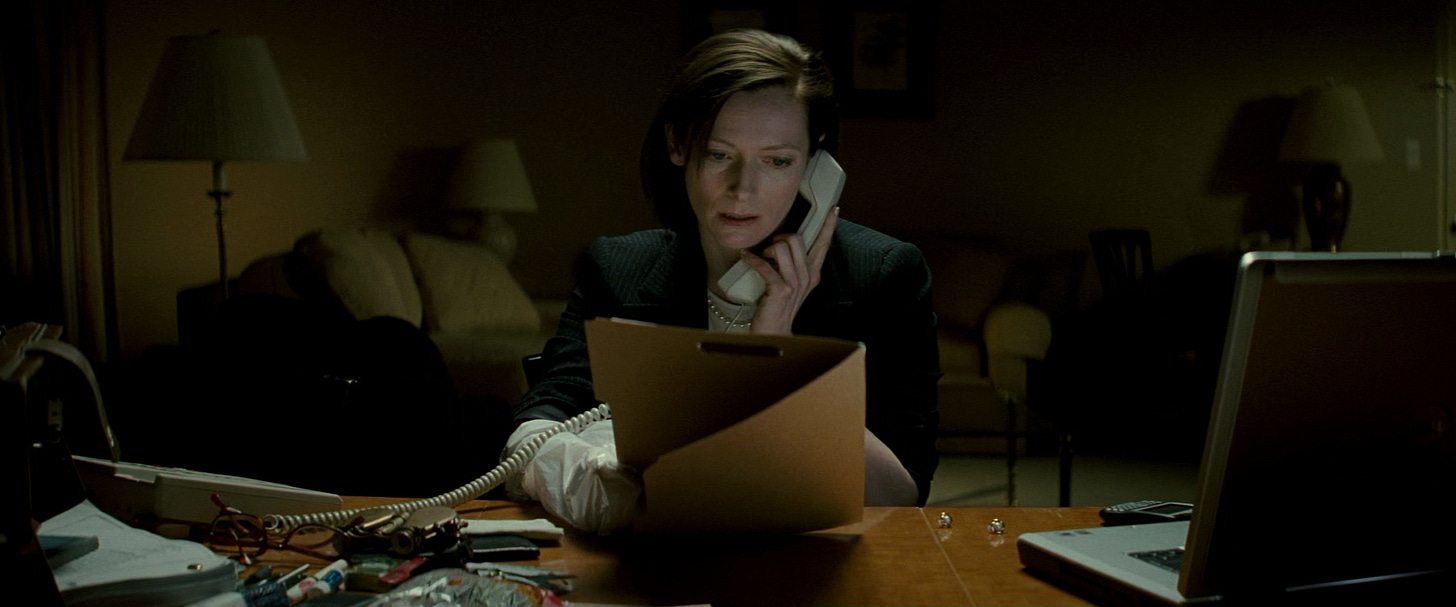

Ever the dutiful janitor, Michael is called in to whip Arthur’s reins. He’s been here before – Nurse Michael – but the stakes are higher, careers and livelihoods and reputations at threat. U/North’s in-house counsel Karen Crowder (Tilda Swinton) feels the threat most keenly. The usual operations of justice – gum up the process, stall, drown the plaintiffs in discovery – no longer seem viable. Arthur has spun out into the world, uncontrolled, uncontrollable. She makes a call.

Bombs in cars, wiretaps, hushed meetings, cheques grubby from greased palms: Michael Clayton has the usual thriller-fodder. Tony Gilroy directs it with a crisp eye and a calm grip. He also found a way to pluck the two-note chord of tension and diversion. All dialogue should have meaning, and Gilroy’s more than most, yet his ace is the minor detail appended to a scene that casts a conversation in revelatory light. Buildup, feint, punchline. He plays a scene for its payoff. The trick’s there disguised, in the first moments, as we’re hustled into the film on the rip of Arthur’s ascending, cresting patter: static shots of law firm hallways, halogen overheads, stationery basket trundles, becoming more peopled as the sequence goes on, filling up with busier subordinates until it’s a zoo of a room, and the final extra hits their mark, slips stage right to slide-reveal Marty being passed a phone with a reporter on the line who somebody has already called a cunt.

Or when Michael steals a few hours at the family home – lawn, leaves, dad with his nasal cannula – and we’re too snared in his whimpers of neglect to notice his brother Gene (Sean Cullen) getting dressed and only at the last, taking a gun from a safe, do we clock that he’s a plainclothes cop. “Human tissue damage” announces the memo Arthur has found, the memo that will screw Karen’s career, screw everyone. So on that snowed-in Milwaukee late-night she has her stilted, too-formal introduction to the assassin Verne (Robert Prescott). But it’s just as we lean in to better hear the scrambler garbling his voice that Karen’s fingers, until now hidden, rise from under the table wearing a plastic bag, as much to avoid planting prints as to protect herself from hazardous goods.

There’s a circular neatness in this. No trash-sack or hazmat or firewall will hold all the poison forever. It leaks, spills, finds its way to your spine. And it might be too trite to say, too obvious, that Michael and Karen are each Janus heads stuck on a single neck. But here they are, reflected, inverse: middle-top and middle-bottom, servants both to the smooth functioning of an unholy gorgon. He fixes super-suavely, with a teenager’s grin and the warm flutter of thickened brown envelopes. She arrives as a squall of panic-sweats and flubbed lines, and tries to solve a problem by killing the problem. Twice. Gilroy has good intuition. Michael Clayton does not glide through gilt boardrooms, looking at the upper strata in cut glass, or probe the velveted chambers of the god-emperors. We glimpse these places, but do not go there. Gilroy suspects, and suspects rightly, that the operations of our superb system are lubricated hourly by minor armies of alternates and underlings, sub-lieutenants and auxiliaries. Real power dwells higher, with their captains: with Marty, with Karen’s superior Don (Ken Howard) and their hushed pressures, their unspoken wishes. The head does the choosing; the hands hold the tools.

And it is their angle to power that governs their choices, sets the limit on their options. Neither Karen nor Michael are secure, fast and immune at the summit of the ladder. The bottom can fall out, the trapdoor giving way. There is always somewhere further to sink. “I’m scrambling,” Michael says, and he is. The restaurant that was supposed to be his one-way passage out from this world has gone bust. A loan shark in gold chain is setting the thumbscrews. Pay up, or lose more. His brother Timmy (David Lansbury) is at fault, one of those helpless saps who only realises they’re an addict when they’re sober, the type to steal tyres and plead in driveways, then disappear. In corner offices, over marble countertops, Michael is told he is essential, vital, necessary: “a miracle worker.” But it never feels like it. The coin he gives away on poker is proof of that. And how much can you trust a lawyer’s word when it’s not signed on paper? He is too low-born, too caught by his skill and by charisma to ever ascend a workman’s station. Michael is someone you have to know, but not someone you should know. Karen doesn’t. “I never heard of him,” she says. “Who is this guy?” It’s a smart prompt for the biographical data we get – Bronx childhood, Fordham Law, Queens ADA. It’s also a question asked incredulously. Michael Clayton isn’t pinging the radar of her ambition, not someone she has to clamber over, or milk for influence.

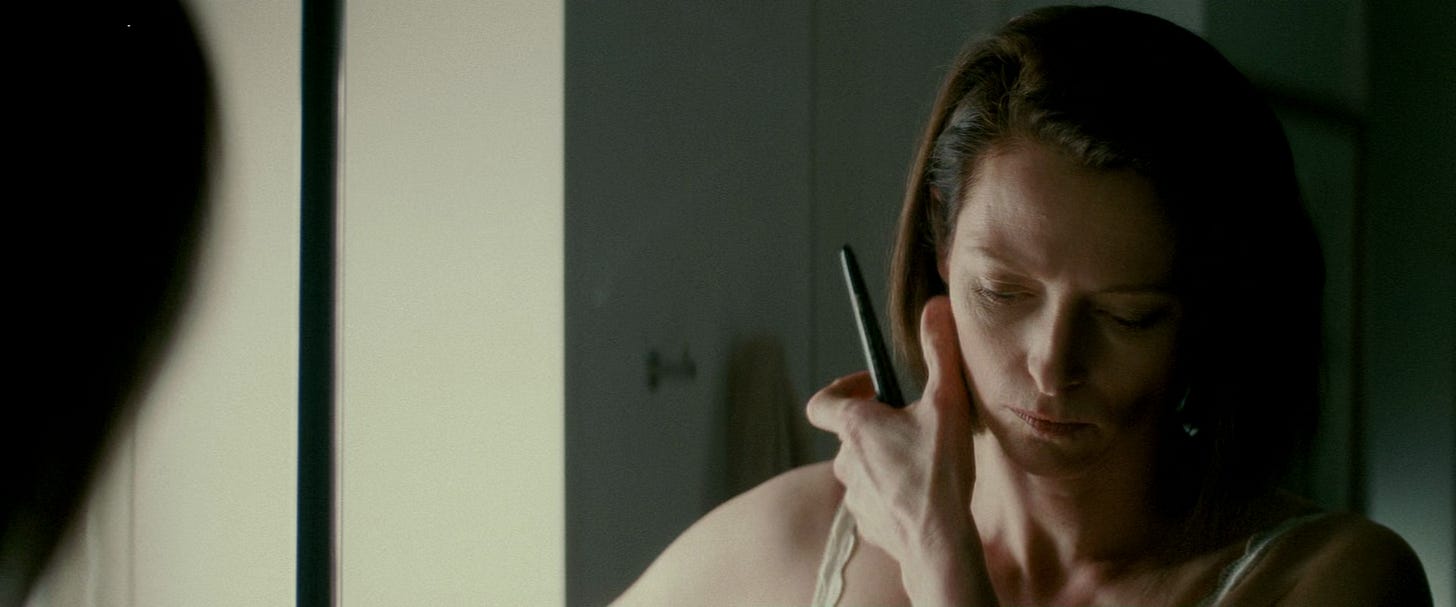

If Karen were anyone else, you might say she was tragic. A striver hollowing her soul to climb the mountain. Except that mountain is made of human skulls and her high heels are slipping in the eyeholes. And it’s a long way down. Painting on a thick veneer of competence consumes her hours. “Balance?” she quips in her trained, forced chuckle. “I think that’s something you search for your whole life.” Vulnerability makes her damp with nervousness, not an innate evil. Precarity, rather than bloodlust, has her dialling the hitman’s number. Swinton plays her on the near fringe of pathetic, always straining to fit the job that feels so large, so important, so male. Such effort has turned Karen into a true believer. Every other character can see the grubbiness of their task, the dirt on their paws. It turns them either mad, or sane, or cynical. As Marty says blithely to Michael: “This case reeked from day one.” But not Karen. Her brain is dropsical, logged with stock response, business cliché, with the fear of being found out. That her smarts were not natural but rehearsed. That she doesn’t really know how this system works after all. Just listen to the perfect smallness of her final line, when Michael is snapping a mouth-open picture on the concourse, the entrapment complete. An alien tongue, baffled: “You don’t want the money?” As if the money could straighten all chicanes, as if it were the only currency of their world, as if the lone product this tender is always guaranteed to buy is silence – the silence of complicity, or the grave.

…I realized, Michael, at that moment, that I had emerged…from the asshole of an organism whose sole function is to excrete the poison -- the ammo -- the defoliant -- necessary for even larger and more dangerous organisms to destroy the miracle of humanity -- and that I have been coated with this patina of shit for the better part of my life and that the stink and stain might in all likelihood take the rest of my days to undo…

FORGET ALL THE GRISHAMS, A Few Good Men, or even twelve angry ones. Michael Clayton is that most subversive thing: the legal thriller in which no laws are obeyed. Their world – this world – is an interior zone unbound by the thing it enforces. Hit-and-runs, class-actions, murder charges: that’s for the schmucks and losers, the dupes dumb enough to get caught, or caught out. You’re either in the circle, guarded behind the closed door, where a janitor is on call to show up in your square-acre kitchen at midnight and mop the spilled blood, or you’re out there, a victim, somewhere in the wastes of America, or wherever, doing your dying uncompensated. On the inside, everyone scratches everyone’s hind. Even Gene, who pleads with Michael to spend more time with the family, who sure looks like a good-cop, hands over a crime scene seal and warns not to be told what it’s for. Serve your function: look the other way. Then there’s Karen, thinking she’s cleared the floor of all threats, pitching the settlement to U/North’s thick wad of shareholders. She does so not for the inherent fairness of the claim, for the righteousness of the plaintiffs’ case, for Anna’s sake. No, what she’s after is the tax write-off. $600million. A deal would (she sneers) “pay for itself.”

Why shouldn’t you go mad, faced with all that? The daily bucketing-out of conscience, the soul encased and compromised, every shared handshake a trade of favour to the injury of someone else. Wearing the extraordinary guise of the late Tom Wilkinson, Arthur introduces the element of insanity to Michael Clayton – the question of who in all this smooth, too-easy seediness is really off their rocker. Arthur, poor Arthur. We’re told he’s mad. Signs of it everywhere. An episode a few years back; the pills set it right. There was a wife, apparently, and a kid, and a more conventional home – one perhaps more recognisable to the gaudy-baroque palette of his partners than the crumbling bohemian studio where he lives and where he will die. Tearing his clothes in a deposition room, shouting wild love for a milkmaid. He has all the obvious marks of mania: the Mach 5 pace of his turmoil, the franticness, the bizzarro behaviour. He inflates everything. Size, scale, crescendo – seventeen baguettes in his bundle – a thousand printed copies of Summons to Conquest – stripping himself to zero – “six years…four hundred depositions, a hundred motions, five changes of venue, eighty-five thousand documents in discovery…thirty-thousand billable hours…and the numbers are making me dizzy…”

The numbers are making all of us dizzy. That doesn’t make him mad. It doesn’t make us mad, either. Doesn’t he keep saying so? insisting? “It’s not just madness…it’s not just madness…It’s not an episode, relapse, fuck-up.” He has breached the chrysalis and happened upon “the most stunning moment of clarity.” Arthur’s pleading, keening, ecstatic rant is one of the finest pieces of monologue writing since Paddy Chayefsky penned Network, and even though it comes clothed in the rags of the unhinged and off-balance, it is by far the soundest and sanest thing said by anyone in Michael Clayton. Most others spend their time backing away from the kind of religious realisation Arthur feels, double-dealing and calling in the goons to protect their position inside the zone. If anyone ever tells you they were made an accomplice against their will, they weren’t aware, that they were following orders, just remember the wilful effort required to keep that place in the pecking order. Truth and lucidity sets Arthur to abandon any feeling of self-preservation. Run headlong at the thing and try to find the off-switch. Arthur is our modern Yossarian: caught in a logical irrationality, he turns to an irrational logic for escape.

But he doesn’t. He can’t. Won’t be allowed. The swift taser in the open door, the quick pill popped in the mouth to paralyse, one-two-three-up carried (single take) to the dying place. The clean, rapid, business-like assassination. The pros at work. It is a peculiarity that Michael Clayton should appear in the same year as another film with an equally plausible – equally terrifying – method of neutralisation. Shooter was a silly movie, though its intent was not far apart from Gilroy’s, and its starring performance was a wire-steel-leather contraption to simulate a self-administered gunshot to the head. Compare that device to the means of Arthur’s murder: Yes, that would be how they’d do it. And Arthur’s paranoia? What’s paranoia when They (Pynchon, reporting) already know what you’re thinking; when a friend can corner you in an alley and naïvely relate what you said on the phone the night before. “He’s a killer,” Michael pleads to Karen early in the film, before he’s realised how wrong he is, before he gets the irony: she’s the only one so diseased as to commission double homicide.

Or maybe Michael knew all along. It was in there, this knowledge, the Arthur-sized seed of doubt. During that scene – one of only two shared between these central characters – Michael has his workwear on, and a brave face, pleading for Arthur’s soundness. Don’t panic he says to a Karen already panicking. Get Arthur his meds and he’ll be back in the saddle. Then Michael lets it slip: you hired him, he says, “because he’s crazy enough to grind away on a case like this for six years without a break.” Crazy enough to be a willing helper to the dangerous organism that is U/North. Crazy enough not to see the damage done by his own hand. Crazy enough to get yourself coated in the shit-patina in the first place.

Michael breaches the same chrysalis, eventually, reborn in the guttering wreck of his exploded Mercedes. He arrives at realisation by a slightly different route than Arthur does. Arthur emerges from madness in a heartbeat – the shock of imminent death before the onrushing traffic that is the setting of his gorgeous, racing oration. Michael approaches slowly, from his own experience, way down in the hierarchy, at risk of losing everything, expendable. Those cursed with the knowledge of how the system functions – those who oil the gears – are blessed in turn with an innate suspicion that the system is up to no good. Yet with this knowledge comes the sobering, daunting thought: the system can’t fix itself, even when the evidence is there, underlined, in bold print, and the case is open-and-shut. Clayton’s just a lawyer, after all. Where are you supposed to turn?

…and do you know what I did next? I took a deep, cleansing breath. I set that notion aside. I tabled it. I said to myself, ‘As clear as this may be -- as potent as this may feel -- as true a thing as I believe I have witnessed here -- I must wait. It must stand the test of time.’

ADVOCACY MOVIES, STIR-THE-heart and to-the-barricades movies, wrap-your-kid-in-cotton-wool movies. There had been a few before. Erin Brockovich comes to mind. After: a flood. Margin Call, The Big Short, 99 Homes. Dark Waters arrived later on. They took the corrosive spill of the Great Recession as their target and subject, poking a long stick in the aftermath. Because of their period, they all had the genetic data of Tony Gilroy’s masterpiece swimming in their cells, the nod of reverence to their betters. But Michael Clayton doesn’t sit so easily alongside its progeny. It’s too slick for that, too knowing. And each of these later films are curtailed by a single fact: they are, to a greater or lesser degree, true stories.

For a true story to get made, it must satisfy in its audience a need for justice, retribution, revenge, transcendence. Their emotional span will always therefore be limited, fated to draw their audience to the trap of believing that the good lawyer, or the far-seeing trader, or the smartarse math-whizz will emerge out the other end on our side, fighting our corner – or at least aware and contrite to the part they played in bringing down the building on our heads. Gilroy ducked that trap. He got the best of all possible worlds. Michael Clayton isn’t a true story, though it feels like it could be, bitten through the skin by real life. And it got there first. Everyone else was scrambling to respond, rushing to note down the feelings and impressions and folktales of the epoch. And there was Our Cleanser of the Hidden Sins, already fully-formed and far-seeing and wise to whatever sense we’d try and make of this collective mess. It has the gift of prophecy.

The film has its own history, of course. Gilroy the journeyman, scribbling his way through dreck, dross, and pulp. He spent years scheming Michael Clayton’s script. There were the usual trials of money, cast, production. Its characters and flow and mood were all born from the 2000s. Had it been made by less talented people, it might appear to us as a relic of the before-time. And it was certainly a coincidence that the film arrived when it did, in the same month when the weather turned and ash began to fall from the sky. But it caught, like a flake stolen from the wind, the temper and timbre of cynicism, of weariness, the hint that all this bright light and polished glass, the mock-grandeur and self-assuredness was opaque, transient, and doomed. The cracks were already starting to show. The well-water really was poisoned, foaming, bubbling over.

And that ending. That exhausted, frightening ending. In style it references The Graduate and The Long Good Friday. But it looks a lot to our eyes like augury, presage. The moment Michael thumps shut the taxi door and orders his fifty buck ride to nowhere: that is the cusp, the hinge, the needle-tip on which our era shifted its weight. Back there, on the sidewalk, it is still October 2007, and will be forever. Inside that taxi, time trundled forward in the Manhattan canyons, skirting the gutters, juddering in the potholes. We’ve been shotgun in the passenger seat ever since, looking rearwards, trying to not flinch, as Michael Clayton passes through the stages of his grief.